Photo Credit:

Photo Credit:

Arkansas Highway & Transportation Department (Date Unknown)

https://bridgehunter.com/ar/lawrence/powhatan/ Date/Source Unknown

Date/Source Unknown

Photo Found on Pintrest

More detailed information needed, especially contemporary newspaper accounts. Buildings in downtown Powhatan were destroyed to make room for the pillars and anchors. Did the townspeople think it was a good idea?

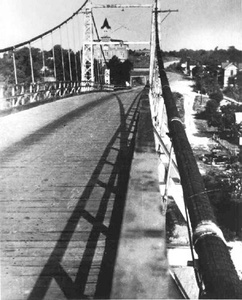

The Powhatan Suspension Bridge was a toll bridge that serviced pedestrians and vehicle traffic from 1926 to 1951.

Background

Powhatan became the seat of Lawrence County in 1869, and people from neighboring Walnut Ridge had to cross the Black River to attend to official business. By the early 20th Century, the people of Arkansas were advocating for better infrastructure, to “lift Arkansas out of the mud,” a push that was spurred by the increasing popularity of the automobile.[1] It soon became clear that the old bridges of the 1800s were not enough to handle the weight of these new machines. Thus, bridge companies realized that a new market had opened besides railroads, and salesmen went everywhere plying their trade. As there were no federal standards yet in place, the bridge companies could design their product to fit each client’s situation, i.e. make the best custom bridge for a specific river.[2] The first mention of a bridge over the Black River was published in 1908, stating that a bill had passed the lower house of congress.1a However, the first talk of a bridge (but not action) was in 1887, planning an iron bridge over the Black River, to cost about 15,000 dollars.1b

Harry E. Bovay and the White River Bridge Company

Harry Elmo Bovay was one of many entrepreneurs in the business. He had already secured a bridge franchise at DeValls Bluff, opening his bridge on January 1, 1925 to much fanfare. It greatly reduced travel time between Memphis and Little Rock. The most important development out of the DeValls Bluff project was the formation of the White River Bridge Company. Bovay filed the articles of incorporation with the Pulaski County Court, on July 21, 1923, transferring his bridge franchises to the company, and recording himself as president. The company began operations with over $500,000 in capital stock.[3]

Powhatan

Since 1906, any river or stream defined as a “navigable waterway” was subject to federal control. Anybody who wanted to build a bridge had to get Congressional approval, and then secondary approval from the Secretary of War and the Chief of Engineers. There are notes in the Acts of Congress for each of Bovay’s bridge projects: Vicksburg, Mississippi; DeValls Bluff and Des Arc, Arkansas; Cario, Illinois. Yet, there’s no act granting him permission to build a bridge at Powhatan specifically. However, on February 12, 1925, Congress did grant Bovay permission to build a bridge “at or near” the town of Black Rock, two miles from Powhatan. It is unclear why Powhatan, the county seat, is not mentioned. Perhaps it is because Black Rock had become more prosperous since the Kansas-Memphis Railroad built a depot there. By April, the issue was still undecided as Black Rock and Powhatan competed for Bovay’s favor.[4] Construction began later that year and completed in 1926.

The bridge was three hundred yards long, fourteen feet wide, and featured barriers four and a half feet tall made of wooden joists. To accommodate river traffic, the bridge rose at an upgrade of fifteen to twenty degrees, which made a distinct arch.[5] According to Evan Smith, a local who was recruited to assist, soil on the Ozark side of the Black River was so rocky that the anchor holes had to be dug by hand. Evans consistently referred to it as "the swinging bridge," because of how it would literally swing whenever someone crossed over. Pedestrians were charged a nickel, automobiles one dollar.[6] [7]

Bovay was successful, but he made enemies in the process. Ferries saw a decrease in business and sued the White River Bridge Company multiple times, and though Bovay won each case, the public wasn’t always on his side. Most people thought the rates were too high, and this issue alone led to a War Department hearing in Memphis in 1930. The rate for automobiles was eventually reduced to seventy-five cents, but public discontent remained.[8]

State Involvement and Decline in Use

The Flood of 1927 and the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 drastically altered the mood of the people towards toll bridges. Road improvements had become a major issue by the end of the decade, and Bovay found himself under growing pressure to sell his bridges to the state. He had rejected Governor John E. Martineau’s offer of $500,000 for his bridge at DeValls Bluff in 1926; he wanted $700,000. His company reorganized and reformed as White River Bridge Corporation in Delaware. The state tried filing a condemnation suit that made its way to the state supreme court over the next few years. For all their maneuvering, the bridge at DeValls Bluff was finally wrested from the company in October 1933.

The bridge at Powhatan didn’t become the target of state designs until Carl Bailey was elected governor in 1937. Eliminating toll bridges was one of his campaign promises. Like Martineau, he tried to buy Bovay outright, offering $120,000 for the Des Arc and Powhatan bridges. Bovay demanded twice that amount. Bailey then deployed some unorthodox methods to attack the bridge indirectly. First, he bought an existing ferry near Black Rock and made it free for public use. He then put signs along the highway encouraging drivers to avoid the bridge. According to one report, the ferry serviced over 3,300 cars between March 27 and April 2, which cost the state $0.05 per car.

Bovay sued the state and got an injunction against them, prohibiting the establishment of any ferry within ten miles of the Powhatan bridge. The state took the case to the Federal Court of Appeals and won. Bovay appealed that ruling, but before the case could get to the U.S. Supreme Court, he finally broke and agreed to sell his final two bridges for $118,955: $68,000 the one at Powhatan and $50,000 for the one at Des Arc.[9] Toll bridges ceased to exist in Arkansas.

Fate and Legacy

Congress granted the Arkansas Highway Commission permission to build “a free highway bridge” at or near Black Rock on July 25, 1939. Bailey was so pleased that he had the Highway Commission’s letterhead inscribed with “Arkansas Welcomes You—No Toll Bridges.” The bridge was left intact, but saw little use. The ferry continued operations until the new Black Rock bridge was finished. The Powhatan suspension bridge was dismantled in 1951.[10]

The old concrete pillars and anchor points are still standing at what has become Powhatan Historic State Park, and there are many people who remember crossing the old bridge. Comments left on www.bridgehunter.com reveal that most did not enjoy it.[11]

“I lived in Paragould, AR, in my teenage years and often with my family we'd travel U.S. 63 between home and Missouri. We never traveled over this bridge; too scary looking, according to my father, and besides, there was a toll. The state operated a free ferry a short distance upriver and we'd utilize that crossing. Whoooeeee! These photos justify my father's fear.”

– J.B. Webster, 1-25-2006

“I was born in 1944 and remember crossing this bridge with my family several times. Always scared. My dad would tell us to hold our breath to make us lighter! Of course we could never last the whole trip.”

– Ron Hutchison, 5-23-2010

“We crossed this bridge sometimes when I was a small boy. It was narrow and high and very scary. The cross planks were always loose and clattered as you hit each one. The longitudinal planks formed two tracks about 2 feet wide where you were supposed to drive. There was a curve in the bridge on the east side, adding to the fear factor. The bridge always shook as you drove along.”

– Bill Rider, 3-26-2012

[1] “Transportation.” The Encyclopedia of Arkansas. http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?search=1&entryID=399 (Retrieved 9-13-2018)

[2]“Bridges.” The Encyclopedia of Arkansas. http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=4208 (Retrieved 9-13-2018)

1a. Batesville Daily Guard (Batesville, Arkansas, United States of America) · 22 Jan 1908, Wed · Page 1 black to be bridged.pdf

1b. Daily Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock, Arkansas) · Tue, Oct 18, 1887 · Page 3 talk of bridge and new courthouse.pdf

[3] “White River Bridge.” Sean O’Riley. Arkansas Historic Bridge Recording Project. 1988. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/master/pnp/habshaer/ar/ar0000/ar0079/data/ar0079data.pdf (Retrieved 9-13-2018)

[4] “Powhatan and Black Rock Seek Black River Bridge.” Arkansas Gazette. April 18, 1925.

[5]Harry Gray v. White and Black Rivers Bridge Company. Bridge Folder. Powhatan SP Archive.

[6] “Evan Smith—Bridge Builder.” Barney Sellers. The Ozarks Mountaineer. May 1991.

[7] “The Doctrine of Creative Destruction: Ferry and Bridge Law in Arkansas.” Michael B. Dougan. Arkansas Historical Quarterly. #2. 1980. P. 152

[8] Ibid. p.153

[9] Ibid. p.155-57

[10] Ibid. p 158

[11]“Powhatan Swinging Bridge.” https://bridgehunter.com/ar/lawrence/powhatan/ (Retrieved 9-13-2018)